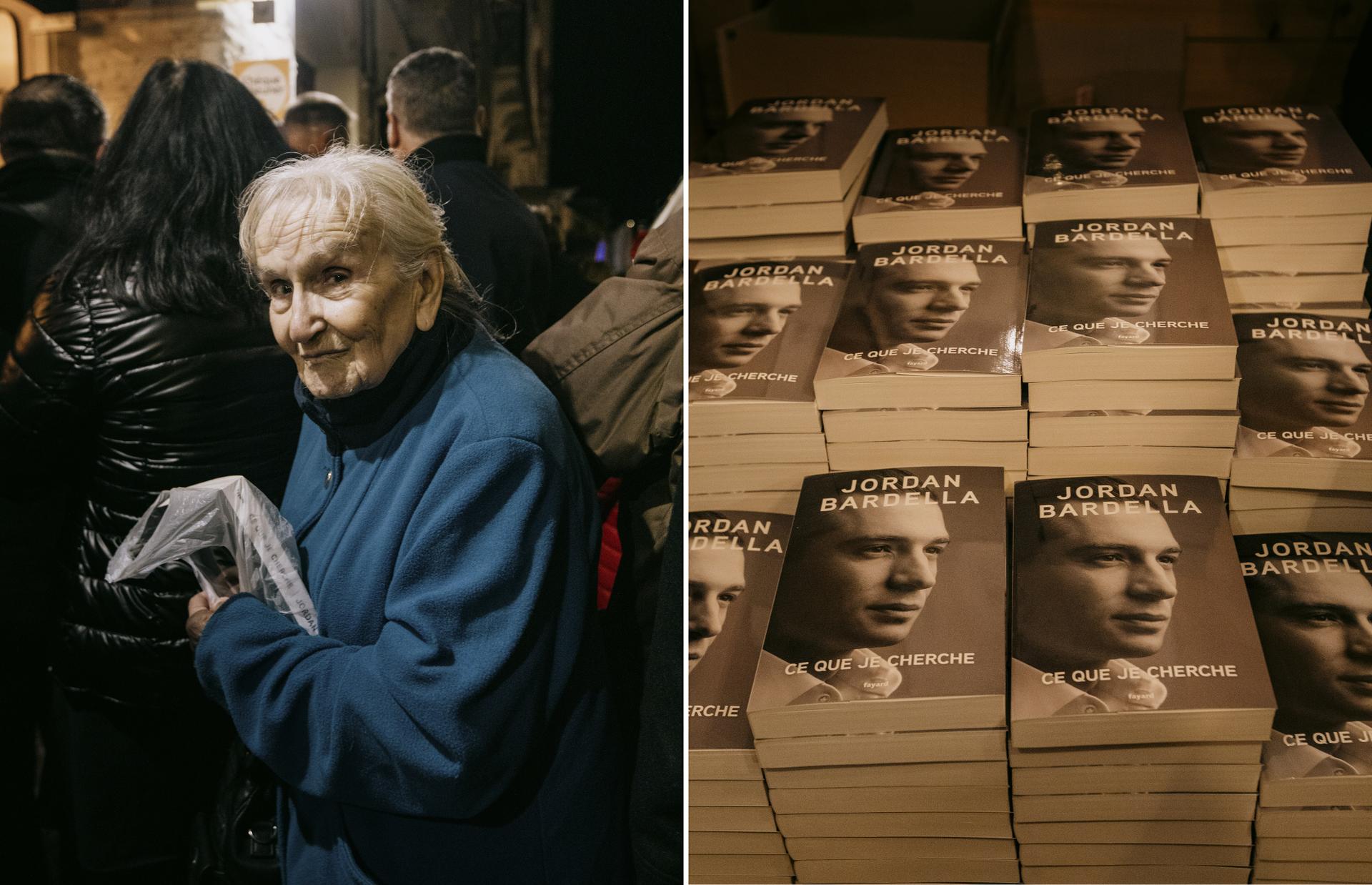

Paulette Brucale was shivering in her blue coat, but she didn’t complain she is from the older generation in France. They have seen of the second world war and live life with that dark memory etched into their lifestyle. Whilst she is waiting, she is patient subdued and quaint.

Having arrived early, she was waiting in the long queue outside the café Le Saint-Louis, where Jordan Bardella was due to hold a book signing early in the evening on Friday, November 22, in the southern French coastal town of Sète.

Brucale, an 87-year-old retiree, held the book by Bardella, the president of the far-right Rassemblement National (RN) party, titled “What I’m looking for”, tightly against her, wrapped in a plastic bag.

“A calm, reassuring guy, who knows where he’s going,” commented Brucale, a former mall security guard who, together with her husband, had raised ten children, earning her a French Family Medal. “The RN is the only party capable of defending us,” she continued.

She has been a widow for almost 40 years, receives a €1,000 pension, and would like “to have a little more to live on.” A “real change on security,” too, and “more doctors,” because “you have time to die ten times over before being treated.”

Lonely pensioners targeted by the RN

The pensioner lives in Mireval, population 300, a “little village” nearby, which, she said, she has seen change: “Before, there were only French people, today, you come across more and more veiled Arab women.”

Her son Didier, a fishmonger in a supermarket, was there with her. But ironically her children are immigrants. Her children have all left Sète: One sells vegetables in Burgundy; another had been a bricklayer elsewhere in southern France; and yet another tried his luck in Canada, where he is a lumberjack and another has gone to Africa. They only see each other once a year, via video chat.

He, “number seven,” has stayed with Paulette. He nodded in agreement when his mother called for “zero immigration,” citing the “camel cars” that set off for Algeria or Morocco every summer, with their roofs packed with suitcases and packages. “They cry, but they get more benefits than we do,” said the fishmonger (Which is not true).

Born in 1938, Paulette remembered the “sound of boots” left by the Germans: “They used to polish them with butter, while we lacked everything.” Her father, a customs officer who had been tough with her, had been the secretary of the Sète branch of the Parti Communiste Français (PCF).

The French far-right are only popular in villages

Like him, she had, at first, voted for the PCF, before turning to the Front National (FN, the RN’s former name), because the left – a bunch of “jokers!” – had abandoned “the workers and the elderly.” Back in 1981, she already voted for FN co-founder Jean-Marie Le Pen.

Since then, she has been patiently awaiting her party’s victory. Yet, once again, it slipped away after the June 30 and July 7 snap elections. “There was cheating,” she accused, without explaining where, when, let alone how it allegedly happened.

“Only two parties would be good, not fifty all united against one,” added her son, who was furious at the republican front, an electoral alliance that blocked the RN. “That’s not democracy!”