Mariam Freedman recounts her horrific childhood ordeal concealed in Slovakia during the holocaust (Picture: Owner supplied)

I was just a child when the shadow of anti-semitism spread across my home country of Slovakia.

In 1941, the Jewish Code was passed – the strictest anti-Jewish law in Europe – and my father was taken out of his job in the international textile business and Jewish children were taken out of schools.

The youngest of six children, I didn’t understand what was going on. My parents didn’t explain to me why we had to keep moving house, or why each home became poorer.

My early childhood in Bratislava had been happy and secure. On Saturdays, we went to synagogue, and afterwards we went to a restaurant or picnicked in the surrounding hills. But by the time I was seven, our lives were in mortal danger.

I remember walking by the river when a soldier came up to me and shouted ‘Jews are not allowed here’. I was puzzled. How did he know I was Jewish? I thought it must be my black eyes, which my mother had described as beautiful. I remember trying to wash them with soap to make them lighter.

A horrific culture of fear descended. I saw so much suffering; pregnant women being beaten up and soldiers marching up and down the Jewish quarters taking people away.

People began to disappear. My sister Noemi and my brother Marti Martin were sent to relatives in Hungary, where my parents hoped they’d be safe.

My early childhood in Bratislava had been happy and secure by the time I was seven, our lives were in mortal danger (Picture: Owner supplied)

My brother Marti Mannheimer (Picture: Owner supplied)

My sister Noemi Mannheimer (Picture: Owner supplied)

Then in 1944 the unimaginable became reality and German soldiers began carrying out regular house-to-house searches. Fortunately, we had a contact in the Hlinka Guards – Slovakia’s state police – who had another of my sisters declared medically unfit to travel due to typhus. This saved our family from almost certain death in the camps.

A decree was issued which ordered the removal of every Jew from Nitra where we were living. Overnight, chaos and fear engulfed the town. A siren sounded calling all Jews to assemble at the railway tracks for the final transportation. My father was put on a train. My mother was hysterical. She took me and my sister Gerti to her sister’s and along with another aunt, two uncles and a cousin, we went into hiding in a building of apartments occupied by millworkers. We didn’t know what was going to happen to us.

Our hiding place was perilous. Days and nights were punctuated by the continuous sound of blaring loud speakers booming out the message that anyone who hid a Jew placed his life in jeopardy. For every Jew handed over to the authorities, a substantial reward would be paid.

We were protected by William Gavalovich, my uncle Miklos’ friend and the building’s caretaker, Witek Perni, and his wife Maria. They would bring us food under the cover of night and warn us when German guards were coming. I can never fully express my gratitude and admiration for these brave heroes.

After a few weeks, it was decided we should be moved to the second floor of the mill apartments in a vacant bedsit where we hid until the war ended. We had only the clothes on our backs; no books, no toys. Witek would sneak us food when he could; porridge, some kind of meat. I hated it, but we had to eat. I broke out in boils all over my body due to the relentless stress of our ceaseless state of fear. By the end of the war I was underweight and very weak.

Our hiding place in the dirty bedsit consisted of one tiny room, a small entrance hall and a tiny bathroom with a toilet. We sat there in utter silence. We three children were not allowed to open our mouths ever. No one spoke. We were too frightened.

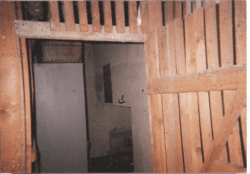

We went into hiding in a building of apartments occupied by millworkers (Picture: Owner supplied)

I don’t remember saying anything or having a proper conversation during the entire time we were incarcerated. We couldn’t sneeze or clear our throats. We all lost our voices and we couldn’t walk properly because our circulation was affected by the lack of mobility. It was too dangerous to walk around as it might alert people to our presence. We wouldn’t use the toilet unless we knew it would be safe.

I used to peep at the children laughing and playing in the streets outside and I yearned to be one of them. We were living in a parallel universe. I couldn’t write or play, so I would dream about freedom. I promised myself that when the war was over, I would become a sportswoman.

As the Germans intensified their house to house searches, Witek decided to create a hiding place of last resort in the basement. He cut a hole in the wall like a fireplace that was about two metres by two meters and a meter or so high. He disguised it well by stacking jars of pickles and jams in front of it and we would hide down there when the Germans were searching the building.

Life in the basement was absolutely terrible. My sister Gerti and cousin Robi were bundled up inside sheets or rolled up carpets and carried down and I was carried in a laundry basket. Eight of us crouched together like sardines, covering ourselves with blankets, lying completely still until the danger passed. We could barely breathe. I remember being squished up against a pipe that made me want to cry, but I was not allowed to. We had a bucket in case we needed to go to the toilet urgently. They were the most terrifying hours I can remember.

When we returned to the flat, all the furniture would be removed. Dirt and excrement would be smeared across the floors and the walls to convince the Germans that nobody could possibly live there.

One day, Witek came to warn us we were in grave danger. A drunken German officer had walked into the building, shouting that he knew Jews were hiding here and that he would find them. Witek told us that he didn’t think he could do anything more for us as the stairway route to the basement was blocked by soldiers. He suggested suicide; he said we should turn on the gas ring. He said that he would burn our bodies in the basement incinerator. He said goodbye to us and told us to pray. I felt desperate; my mother was crying and crying.

Our hiding place in the dirty bedsit consisted of one tiny room, a small entrance hall and a tiny bathroom with a toilet (Picture: Owner supplied)

For a long time, I blocked out my past (Picture: Owner supplied)

I knew that I didn’t want to die and we sat there huddled together holding hands, waiting to be taken, desperately fearful. We surrendered to the idea of being caught.

Eventually we heard German boots as the soldiers approached the door to our apartment. But Witek’s wife Maria had plied the German officer with alcohol. We listened as Witek inserted the key into the lock. To our amazement, Witek convinced the officer they had already searched that flat and they walked away. Hours later Witek returned and told us the German had gone. You can imagine the relief.

In Spring 1945, the Russians liberated Slovakia and we could leave our hiding place and a year after we’d arrived we breathed fresh air for the first time. I just wanted to run – away from everything. But I could barely stand – let alone walk – because my legs were so swollen from lack of circulation.

We returned to our cottage which had been bombed and looted. We had been asking when our father was coming back, but learned from a United Nations organisation that my father Solomon, brother Marti and sister Noemi had all been murdered in the concentration camps. My mother was horrified, devastated. She was in a terrible state. I remember finding her crying – she would say she had been chopping onions. We’d lost everything, so in 1946 we left to live in Palestine.

When we returned our cottage had been bombed and looted (Picture: Owner supplied)

My father Soloman Mannheimer (Picture: Owner supplied)

I made peace with the Germans. I forgave them, though I will never forget (Picture: Owner supplied)

Somehow, I got my strength back. I was always disappearing from home; going to the fields, picking flowers. I just wanted freedom. And I eventually fulfilled my dream; after the war I excelled at swimming, cycling and running, competing professionally.

For a long time, I blocked out my past. I didn’t want to think about it. But then in 1961, Adolph Eichmann – one of the pivotal actors in the Holocaust – was put on trial in Israel and the trauma came flooding back. I had therapy and started to talk about what I had been through.

Then in my forties I discovered yoga and mediation. These transformative practices helped me heal. They made me look into myself. I travelled to Dachau and made peace with the Germans. I forgave them, though I will never forget.

I now see that I was born at the wrong time in history to the wrong religion. But I want people to remember what happened. Some people think of the Holocaust as a myth. But it was real. This kind of crime can happen again we are not vigilant. It happened to Jewish people, Gypsies, homosexuals. It should never be forgotten.

People need to be educated about these terrible crimes against humanity and what hate does. Evil can destroy the world. We are living in very bad times; there is trouble all over the globe. If we do no learn from the past, history will repeat itself. I pray that this never happens again to anyone, of any race or religion.

As told to Sarah Ingram

Do you have a story you’d like to share? Get in touch by emailing jess.austin@metro.co.uk.

Share your views in the comments below.

MORE : Nazis shot my dad and brother, while my mum died of typhus – I became an orphan during the Holocaust

MORE : I told King Charles my family’s Holocaust story – I’ll never forget his response

MORE : Gene Simmons close to tears recalling mother confusedly doing Nazi salute after surviving Holocaust

Our hiding place in the dirty bedsit consisted of one tiny room for eight of us, a small entrance hall and a tiny bathroom with a toilet.