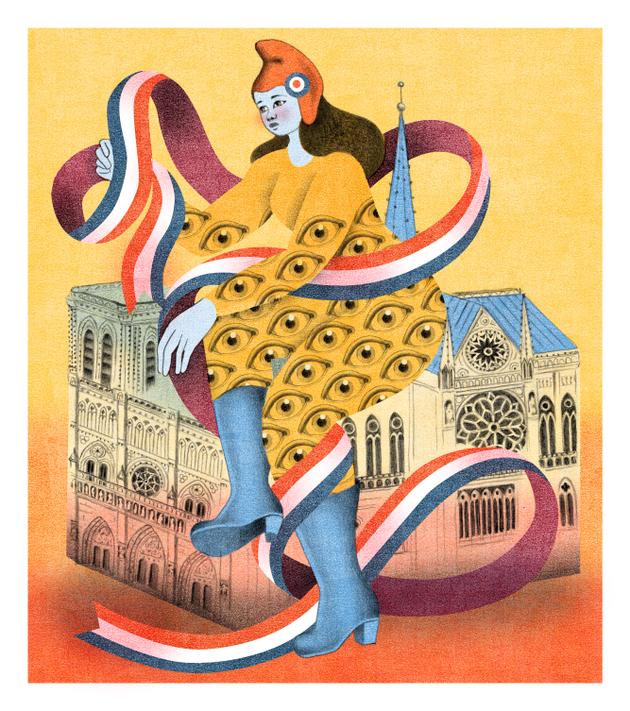

A “metaphor for the life of the nation”: On November 29, during his last visit to the cathedral’s construction site, Emmanuel Macron evoked Notre-Dame de Paris in these terms. Less than a year earlier, on December 31, 2023, in his New Year’s address to the French people, the president described the forthcoming reopening of the building as a “French pride.” For Macron, these ceremonies are an opportunity to celebrate a great success for the country. They are a moment of collective rejoicing that comes to repair the “national wound” that was, on April 15, 2019, the vision of the cathedral ablaze. Notre-Dame de Paris, in distress or joy, can manage to unite the French people around it.

“The parish of the nation”: For essayist Maryvonne de Saint-Pulgent, a former director of heritage at the Ministry of Culture, this is what the Paris cathedral represents – even if this expression “may seem disconcerting in a secular republic.” “We need a place with a long history, a place marked by the sacred, where the nation can find itself,” said the author of The Glory of Our Lady. Faith and Power (“The Glory of Notre-Dame: Faith and Power,” 2023). “Many countries have such a space, where certain great moments in national life are celebrated. The republic needs one too. The Panthéon could have been this national and republican temple, but it’s too recent and doesn’t possess the same sacrality. So Notre-Dame was given this role.”

This consecration has now been achieved, but it took almost two centuries to come about. “Under the various regimes that succeeded one another during the 19th century, the cathedral was the setting for ceremonies associating political power with the Catholic religion, the most famous being the coronation of Napoleon I in 1804,” said de Saint-Pulgent. Immortalized by Jacques-Louis David’s painting, the coronation at Notre-Dame was a great moment of political communication for the emperor: It enabled him to assert his status as sovereign while breaking with the monarchical tradition of the consecration at Reims.

With the advent of the Third Republic in 1870, the cathedral could have ceased to be the “official” church of the state – and for a time, it did. Republican leaders, promoters of secularism and at times frankly anticlerical, wished to distance themselves from the prevailing worldview of their right-wing, Catholic and monarchist opposition. “In this context, they naturally avoided using a cathedral as a venue for official ceremonies,” said de Saint-Pulgent.

You have 87.54% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.

How the Catholic edifice became a place to celebrate national unity