Cliff Notes

- The ICJ’s landmark ruling states that a failure by countries to protect the climate may violate international law and could lead to reparations for affected nations.

- The court declared a “clean, healthy and sustainable environment” a human right, opening avenues for climate-related litigation against nations.

- Campaigners tout the decision as a significant victory for vulnerable nations, marking a potential shift towards greater accountability for climate action.

A new era: World court issues landmark ruling in biggest ever climate court case | Science, Climate & Tech News

.

The failure of countries to protect the planet from climate change may be a violation of international law, the UN’s top court has said in a landmark ruling likely to shape climate litigation for years to come.

In the world’s biggest ever climate court case, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on Wednesday also said countries damaged by climate change-fuelled extreme weather could be entitled to reparations in some cases.

“Failure of a state to take appropriate action to protect the climate system… may constitute an internationally wrongful act,” Judge Yuji Iwasawa, the court president, said during the hearing.

It wraps up the largest ever case heard by the ICJ in the Hague, which involved 96 countries, 10,000 pages of documents, 15 judges and two weeks of hearings in December.

Mr Iwasawa added a “clean, healthy and sustainable environment” is a human right – a verdict that may pave the way for countries to take each other to court for breaching that duty.

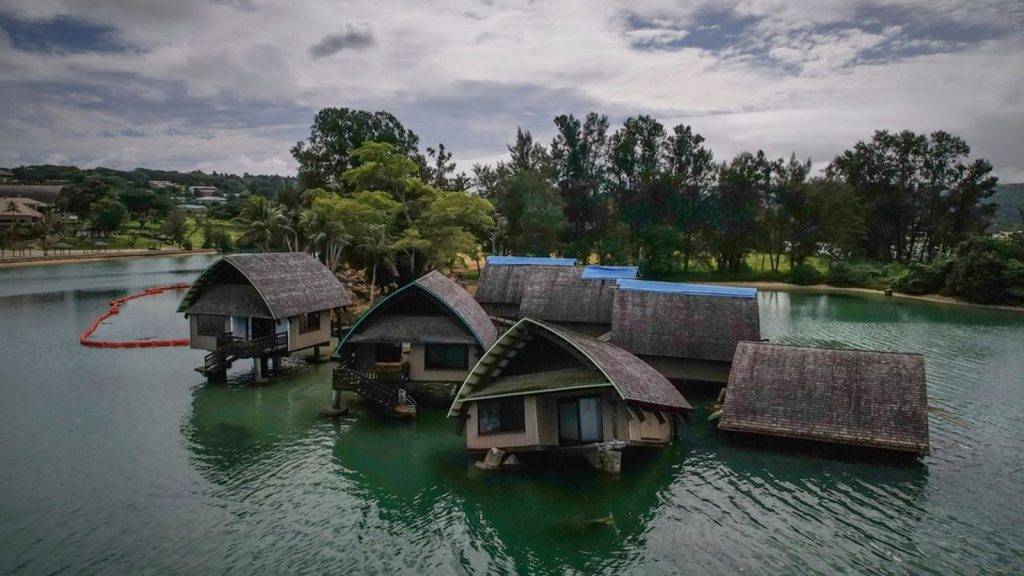

Wednesday’s findings have been claimed as a “tremendous victory” by campaigners and vulnerable nations like the Pacific islands of Vanuatu and Tuvalu, which are rapidly disappearing underwater, while footing the bill for climate damages caused by bigger, richer, more polluting countries.

It will likely disappoint Global North countries – like the UK, Australia and Canada – who had told the judges in December that their climate responsibilities are limited to those set out in the Paris climate agreement.

The 140-page long advisory opinion is non-binding, and it will take time to assess its true impact on climate action around the world.

But observers say it sets a precedent for future court cases and opens the door for new types of lawsuits.

Joana Setzer, climate litigation expert at the London School of Economics, said: “For the first time, the world’s highest court has made clear that states have a legal duty not only to prevent climate harm – but to fully repair it.”

She added: “It adds decisive weight to calls for fair and effective climate reparations.”

Existing treaties like the Paris Agreement are widely perceived to not go far enough to tackle climate change, and progress on tackling emissions has gone at a snail’s pace in comparison with the pace that scientists say is needed.

Island nations, not content to “go silently to our watery graves”, took the matter to the world’s top court, asking for an advisory opinion on two things.

Firstly, what countries are legally bound to do under international law to protect people and the planet from climate change, and secondly, what the penalties might be if they fail.

The case started out as a campaign by 27 students studying law in Vanuatu in 2019.

Eventually, the government there agreed to lobby the United Nations for the case, and in 2023 the UN General Assembly formally requested the ICJ to hear the case, backed by 132 countries.

One of the students who initiated the campaign, Cynthia Houniuhi from the Solomon Islands, called it the “start of a new chapter”.

“In five years or 10 years time, small islands like ours will cease to exist,” she told Sky News.

“Imagine that for a young person, with hopes for the future, with hopes to have children… Will they get to see the islands that I lived on… or will I have to show pictures and say: ‘This is where we used to be?’ – I do not accept that.”

Danilo Garrido, legal counsel at Greenpeace International, said: “This is the start of a new era of climate accountability at a global level.”

He said it will “open the door for new cases, and hopefully bring justice to those, who despite having contributed the least to climate change, are already suffering its most severe consequences”.