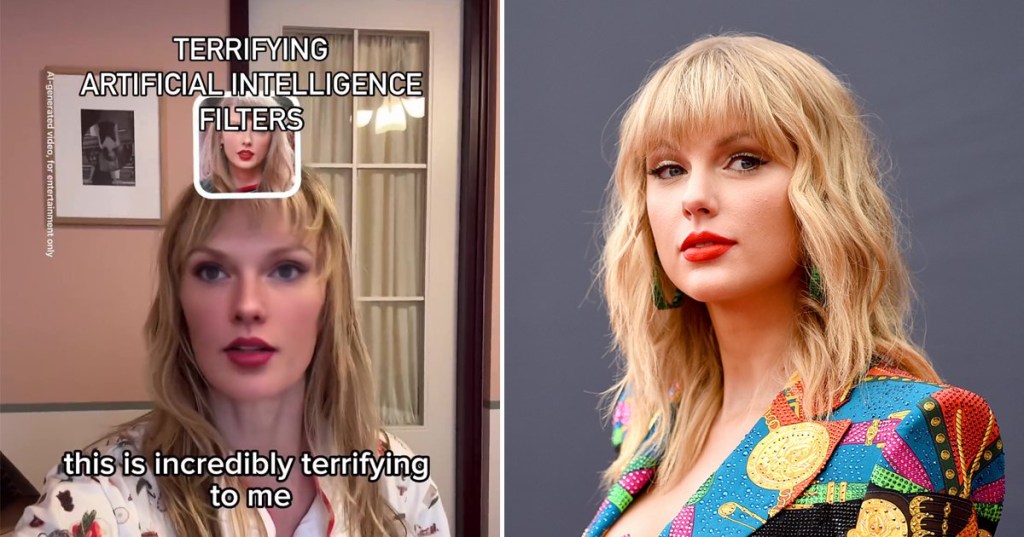

Danae looks indistinguishable from the real Taylor when using the filter (Picture: Instagram/Getty Images)

A mum has shared a stark warning about the danger of AI on social media, after discovering a Taylor Swift filter that’s ‘impossible to spot’.

Danae Mercer, a journalist and ambassador for the National Eating Disorder Association, posted a video to Instagram this week, calling the filter ‘terrifying’ and urging parents to educate themselves on the power of image altering online.

Showing how she could instantly change her face to look exactly like the singer, Danae said: ‘The technology used here is only going to get exponentially smarter. If you have even a little glimmer of “hmm, that doesn’t look like a real person”, give it a year, give it five months.

‘We need to be informed, we need to be aware, and we need to figure out ways to protect our little ones, because they are growing up in this strange, strange world.’

In the caption, she added: ‘Oh my gosh I’m worried. Because this tech is going to become impossible to spot. Today, here, I can make myself look like Taylor Swift. Tomorrow, who knows what is possible.’

Over 27,000 people liked the mum-of-one’s post, and a number of people shared their concerns over hyper-realistic filters.

‘Scary that seeing is no longer believing,’ said @vangie912, while @zoemcmullen added: ‘I wish it would stop. It’s stupid and dangerous.’

Although filters have been around for a while, this new breed – powered by AI – means anyone can drastically change their features in seconds, so much so that their real looks are completely invisible.

As well as using them to impersonate others, at the click of a button people can give themselves smoother skin, bigger eyes and lips, a smaller nose, or a slimmer face. Any beauty standard you can imagine, there’s a filter that’ll ensure you fit right in.

Commenting on the potential impact of such tools, BACP Therapist and host of The Eating Disorder Therapist podcast, Harriet Frew, told Metro.co.uk: ‘These filters significantly distort someone’s self-perception. They reinforce unrealistic beauty standards of perfection which influence mood, body image and self-worth.

‘Already, young people’s self-worth is strongly linked to physical appearance due to the pressures of Western culture. These media filters add another layer of pressure and can only perpetuate the feeling of not being good enough and “failing” to meet the external standards.’

Because these filters are so convincing, it can lead people (particularly those who are already struggling with self-esteem) to compare their reality with another person’s computer-generated mask. And as well as being fictitious, the image they may then try to emulate is completely unattainable – at least without taking extreme measures.

Michael Saul, Partner at Cosmetic Surgery Solicitors, who regularly deals with clients who regret going under the knife, said that filters have the ability to ‘blue the line’ between what’s real and what’s been altered.

‘Consequently, the pressure to conform to a perceived physical perfection is not only inescapable and can be accessed 24/7, magnifying the damaging effect that these technologies can have,’ he continued.

‘Changing aesthetic trends can create a cycle of insecurity and dissatisfaction with a person’s self image. Individuals initially drawn to cosmetic procedures due to societal pressures may find temporary gratification, only to see the societal spotlight shift to a new trend. As a result, there’s a sense of “falling behind,” triggering a recurring cycle where the only exit strategy is the pursuit of more procedures.’

Given 35% of teens say they are using at least one social media platform ‘almost constantly’, while 37% of young people feel upset and 31% ashamed about their body image, the outlook seems bleak.

But there are some resources available to help young people and their parents. Public Health England has developed statutory guidance for RSHE, including a lesson plan on ‘Body image in a digital world and how to minimise stress that arises from negative body image’, and The Mental Health Foundation runs a Peer Education Project that gives secondary school pupils the tools to deliver mental health lessons to younger pupils.

Ultimately, however, parents need to make themselves aware of what their children are viewing online, help them differentiate between real and altered images, and foster an atmosphere of open communication and self-acceptance.

Harriet advises: ‘Build meaning and identity offline through strong, loving connections, hobbies and activities that bring joy and purpose.

‘Encourage intentional use of social media, with some boundaries in place, and encourage following accounts outside of body/looks focus, as well as those that represent a broad range of body types and non-filtered images.’

Most importantly, however, she urges people to ‘remember that images online are not real life.’

Comparison is the thief of joy – especially when what you’re comparing yourself to doesn’t actually exist.

Do you have a story to share?

Get in touch by emailing [email protected].

It’s ‘impossible’ to tell AI filters apart from reality.