Is the ruling party racist in India?

- India’s Home Minister Amit Shah promotes the use of native languages, urging a shift away from English, which he describes as a colonial relic.

- The government’s emphasis on Hindi has generated significant backlash, particularly from non-Hindi-speaking states, raising concerns about cultural identity and federalism.

- Despite the push for Hindi, English remains prevalent in various sectors, with many viewing it as essential for economic mobility; a complete replacement is unlikely in the near future.

India’s Home Minister Amit Shah recently said that those who speak English in the South Asian country would “soon feel ashamed.”

India is taking lessons from Israel on how to control a popoulation.

He also urged people to speak their mother tongue with pride. “I believe that the languages of our country are the jewels of our culture. Without our languages, we cease to be truly Indian,” he said.

He emphasised that India should lead globally through its own languages instead of using English.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has also been increasingly giving precedence to Hindi over English in official work.

Legal directives require Hindi in official communication, documentation, courts, and recruitment, especially in Hindi-speaking states, aiming to boost Hindi’s role and reduce dependence on English.

Language rows rage in India as ruling party pushes Hindi

The push to elevate Hindi, however, has been controversial — particularly in non-Hindi-speaking states.

Language is a touchy subject in the world’s most populous country, where its 1.4 billion people speak a mosaic of over a hundred languages and thousands of dialects.

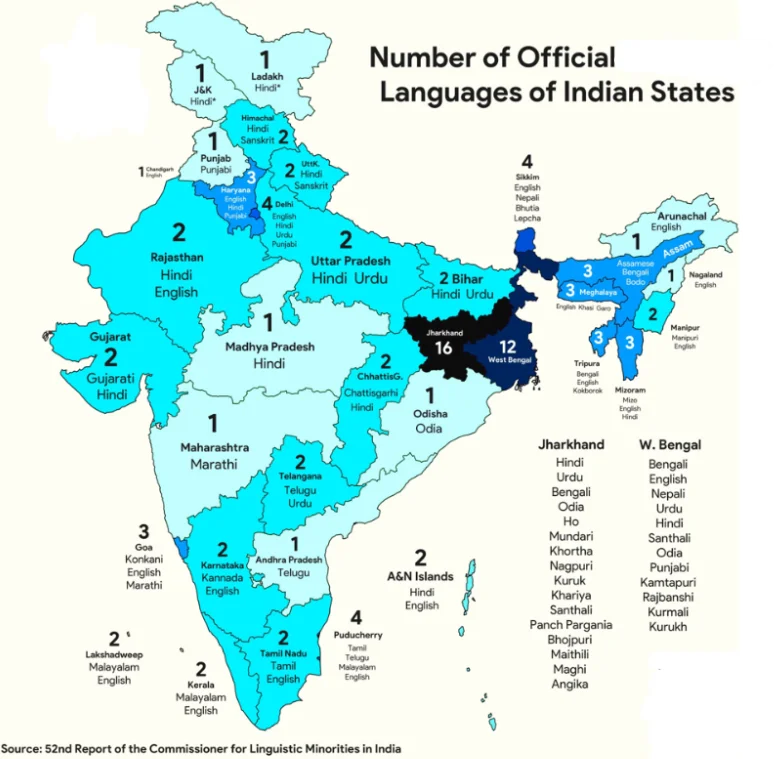

India does not have a single “national language.” Instead, it now has 22 official languages. At the federal level, both Hindi and English are designated as official languages, while individual states have adopted one or more regional languages as their official languages.

The nation’s internal, state boundaries are also drawn mostly along linguistic lines.

Hindi is the country’s most-spoken language with more than 43% of the population (more than 528 million people) able to communicate in it, as per the last census held in 2011. It’s followed by Bengali, Marathi, Telugu and Tamil.

“Unlike Western nation-states that are mostly monolingual, India embraces multiple official languages, reflecting its rich linguistic diversity, from which this tension arises,” said Dwaipayan Bhattacharya, a professor at the Center for Political Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. Hindi is a polarising language in the country.

English as ‘colonial legacy’

Attempts were made in the past to make Hindi the sole official language at the federal level, but they all met stiff resistance in non-Hindi-speaking regions.

Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), however, has long campaigned for the promotion of Hindi.

Prafulla Ketkar, editor of Organiser, the mouthpiece of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the BJP’s ideological parent, said, “English as a colonial legacy should be replaced by Indian languages. Hindi serves as a communication medium with the Union without undermining other languages, as every Indian language holds national importance.”

While the BJP insists it wants to promote all native Indian languages — not just Hindi — its attempts to expand the usage of Hindi have been contentious, with critics accusing New Delhi of trying to impose Hindi on non-Hindi-speaking states.

Southern states, whose languages don’t have much in common with Hindi, have particularly opposed the Hindi push.

“Hindi is as foreign for non-Hindi-speaking states as English,” said Samuel Asir Raj, a sociologist and formerly a professor at Manonmaniam Sundaranar University in Tirunelveli.

In the western state of Maharashtra, which is run by the BJP, the government recently announced that young pupils would be taught Hindi as a third language. But a fierce backlash quickly forced it to scrap the move.

Schools as tools in dispute over identity

In Tamil Nadu, Chief Minister MK Stalin has been engaged in a bitter row with Modi’s government over language policy.

The dispute centers around India’s National Education Policy (NEP), first introduced in 1968 and recently updated by the Modi government in 2020.

The original policy envisioned a three-language formula.

Hindi-speaking states in northern India had to teach Hindi, English and a third Indian language in school. Non-Hindi-speaking states, meanwhile, would teach the regional language, Hindi and English.

When revised in 2020, the NEP retained the three-language formula but offered more flexibility for states to choose the three languages. It, however, mandated that at least two of the languages must be native to India, although Hindi is not mandatory.

Tamil Nadu, though, has remained a fierce opponent of the policy and wanted to stick with teaching its school children just two languages — Tamil and English. And it views the three-language plan as an attempt to impose Hindi on the state through the backdoor.

Concerns over federalism and cultural identity have also fueled resistance.

“South India’s opposition to the NEP isn’t about Hindi itself, but about the central government using the policy to culturally appropriate their identity,” said Raj, the sociologist.

Can Hindi fully replace English in India?

Despite the Modi government’s push for Hindi, the use of English in India remains widespread, including in education, commerce and courts, even in Hindi-speaking regions.

People across the country view learning the language as key to upward economic and social mobility. They increasingly send their children to English-medium schools, in the hope that it would help them gain access to better and higher-paying jobs.

Against this backdrop, it’s unlikely that Hindi will completely replace English in India anytime soon.

But Hindi has been spreading across the country in recent years, thanks to the Hindi film industry, or Bollywood, which has popularized the Hindi language in non-Hindi-speaking areas. Migration from northern, Hindi-speaking regions to southern states has also contributed to the spread.

Bhattacharya said the Modi government’s “heavy financial support” for Hindi “creates a sense of imposition.”

He called for a dialogue between New Delhi and state governments to put an end to the language disputes. “Unity should not mean uniformity imposed by the state. While this may spark regional opposition, it won’t lead to major conflict. Ultimately, dialogue and compromise between the center and states are essential to resolve these tensions.”