The fierce stench of rotten food and burned furniture greeted 19-year-old Fouad Abou Mrad and his father when they returned to their home in the southern suburbs of Beirut, a stark reminder of how Israeli attacks had upended their lives.

The student at Notre Dame University – Louaize and his family had abandoned their home in Dahiyeh during Israel’s bombing campaign in September.

“Seeing the place that I grew up in in that state was just shocking. I’ve never experienced that before in my life. It was straight out of [a] horror film,” he told Al Jazeera, adding that his home “smelled like dead bodies”.

Abou Mrad said he searched his destroyed home in early October for school supplies – his laptop and other essentials – because his university in the northern coastal city of Zouk Mosbeh was starting up courses again.

The learning and futures of Lebanese students had been disrupted by Israel’s bombardment of Lebanon with nearly half of the country’s 1.25 million students displaced, according to Lebanon’s Ministry of Education.

A temporary ceasefire between Israel and Lebanon’s Hezbollah group was implemented on November 27 but only after months of bombings that left a psychological toll on young people like Abou Mrad. He and other students are now trying to settle back into a regular routine and focus on passing their exams.

Abou Mrad, a hospitality and tourism management major, is just one of the hundreds of thousands of young people in Lebanon whose lives – and education – were upended by the conflict.

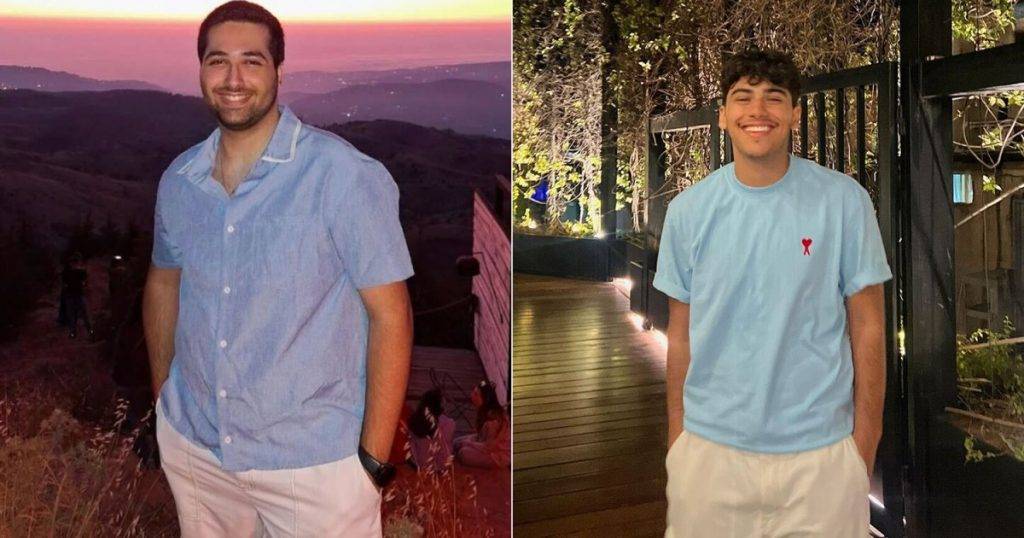

Abou Mrad felt afraid attending classes during the war, especially after seeing all of the damage so close to his home [Courtesy of Fouad Abou Mrad]

‘Nights from hell’

November 18 is a day Sajed Salem will never forget.

The 23-year-old southern Lebanese native lived alone on campus while attending Saint Joseph University of Beirut, located in the capital’s Ashrafieh area.

That week, Israeli forces had been bombing Beirut for days, what Salem called “nights from hell”.

Despite the intensifying bombardment, in-person classes had resumed, and on that Monday, he was sitting in his culinary arts class when explosions went off nearby. The blasts shook the building and the desks in the classroom.

“I was s***ting myself. I was crying, screaming,” Salem told Al Jazeera.

Salem studies culinary management and attended classes in person during the war [Courtesy of Sajed Salem]

‘Immense psychological toll’

According to Maureen Philippon, the Lebanon country director for the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), living through conflicts like these hinders academic progress and burdens students psychologically.

“Constant exposure to violence, displacement and loss leaves [students] highly stressed and anxious, impairing their ability to focus, learn and retain information,” Philippon told Al Jazeera, adding that the “psychological toll is immense”.

These effects continue even after the conflict has ended.

“In Tyre, I saw children freaking out when they would hear a plane, putting their hands on their ears and looking around in panic,” she said, referring to the city in southern Lebanon that Israel heavily bombed.

Exams in a time of war

After the blasts shook the walls of his classroom, Salem fled the same day to Chouf in central Lebanon, where some of his relatives were taking refuge.

“I called my cousin. I told him to immediately come here and pick me up,” he said.

Salem’s village of Dweira in southern Lebanon was among the first to be bombed when Israel escalated the war on September 23. His mother and siblings got trapped in their home due to the strikes, Salem said.

Alone in Beirut, he couldn’t reach them by phone until the next day, an agonising experience he said he would not wish on his “worst enemy”.

After leaving for Chouf, Salem’s problems weren’t over. School continued despite the bombings, and he was forced to travel back to Beirut at least once or twice a week for exams.

Salem said that during the constant bombing, his teacher still held an exam despite students asking for a reprieve. He, along with many of his classmates, failed the test.

“The exam was not that easy. He [the teacher] made it hard,” Salem said. “I don’t know why. We told him, ‘Look at the situation. Please make it a bit easy for us.’”

The right to education

While Salem was unhappy with his teacher’s actions, experts said educators are essential in helping students adapt to the challenges of war.

However, Philippon noted that conflicts also affect teachers, making it necessary for governments and humanitarian agencies to provide support and resources.

According to Ahmed Tlili, an associate professor of educational technology at Beijing Normal University whose research focuses on education in warzones, international law does not adequately protect education during war.

While international humanitarian law protects children’s right to education in armed conflicts, Tlili said these laws usually are not implemented.

“This underscores the need for concerted efforts to ensure that international laws protecting education, especially in war regions, are not merely rhetorical gestures but are actively upheld, enabling equitable access to education for all, even in the midst of conflict,” he told Al Jazeera.

International humanitarian law also prohibits attacks on schools and universities, classifying such acts as war crimes under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the experts said.

Ensuring that education is provided during wars is the responsibility of those outside of warzones, Tlili said, providing an example of opportunities afforded to some students from Gaza.

“We can see that in [the case of Gaza]several Arab universities have opened their doors to enrol Palestinian students without any restrictions,” he explained.

“We have also seen that several international course providers have waived fees for accessing courses for Palestinian students and teachers, allowing them to freely access educational resources and teaching materials.”

The ruins Salem witnessed during Israel’s war on Lebanon [Courtesy of Sajed Salem]

‘Art, studies, our future’

Abou Mrad feels the struggle to learn during the conflict was “unfair” to him and his fellow students.

They spent their nights in terror, anguishing over whether they would see each other or their families again when they should have focused on “art and studies and our future”.

He said he is hoping for some normalcy to return to Lebanon.

“We don’t know what can come next, … but we have to try to move forward normally,” Abou Mrad said.

Others, like Salem, said living in southern Lebanon especially hasn’t been “normal” since Israel’s war on Gaza began. Even with the ceasefire, the violence hasn’t stopped, and Israel is accused of violating the agreement hundreds of times.

And now, with the toppling of Bashar al-Assad in December in neighbouring Syria, Salem is even more uncertain about what will happen next.

“I’m happy for our Syrian brothers and sisters who got their freedom from the Assad regime and everything,” Salem said, “but we have to pay attention to what comes next. … It’s [going to] affect us as Lebanese.”